The electromagnetic railgun developed by BAE Systems for the U.S. Navy has a lot going for it. It is smaller than a conventional cannon. It can fire a projectile up to 4,600 mph, or around Mach 6. It uses no gunpowder or chemical propellants, eliminating the need to carry dangerous explosives on a warship. The weapon has the potential to hit a target over 100 nautical miles away.

But America's supergun, as the Wall Street Journal called it, has two major complications. As Defense One recently pointed out, the weapon takes an enormous amount of power to fire, and it literally tears itself apart with use. The EM railgun has already been in development and testing for over a decade with total costs exceeding $500 million for the project.

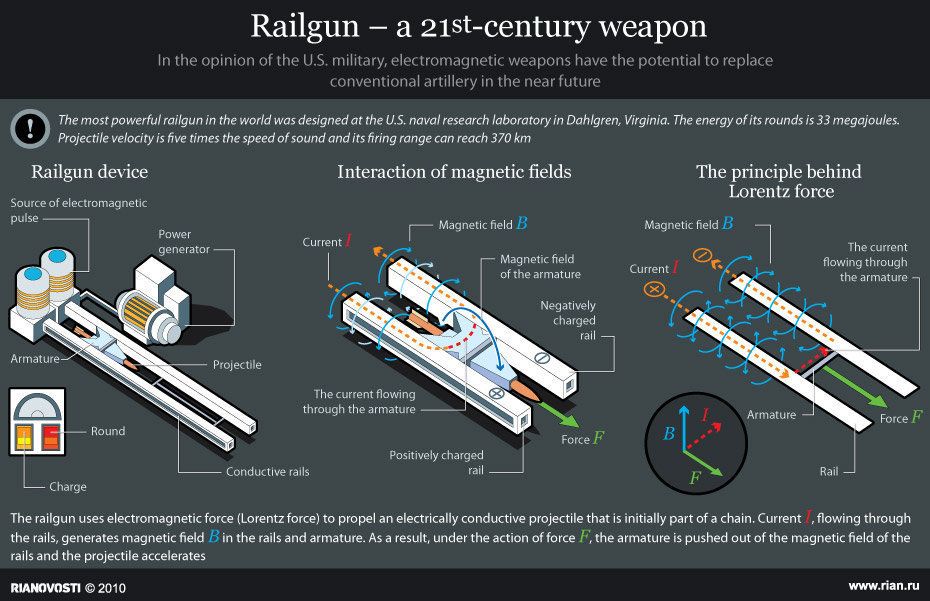

The railgun works by storing power generated from an external source, like a ship, for several seconds. After the weapon is brimming with some 32 megajoules of energy, its capacitors send an electric pulse down two long rails, one negatively charged and one positively charged, generating an electromagnetic field that fires the projectile along the two rails. The 25-pound projectile is a non-explosive bullet filled with tungsten pellets inside an aluminum alloy casing, or sabot, that falls away after the projectile leaves the barrel. The Navy is also developing resistant electronics that go inside the projectile to make it possible to aim the weapon with GPS, technology that could eventually give the EM railgun effective missile-defense capabilities.

The problem is that the only ships that will be able to generate the gargantuan 25 megawatts of power (enough to power almost 19,000 homes) required to fire the railgun are the Zumwalt-class destroyers, which will use Rolls-Royce turbine generators to produce as much as 78 megawatts of power for the ship. Only three of these technologically advanced warships will be produced, the first being the USS Zumwalt currently undergoing sea trials.

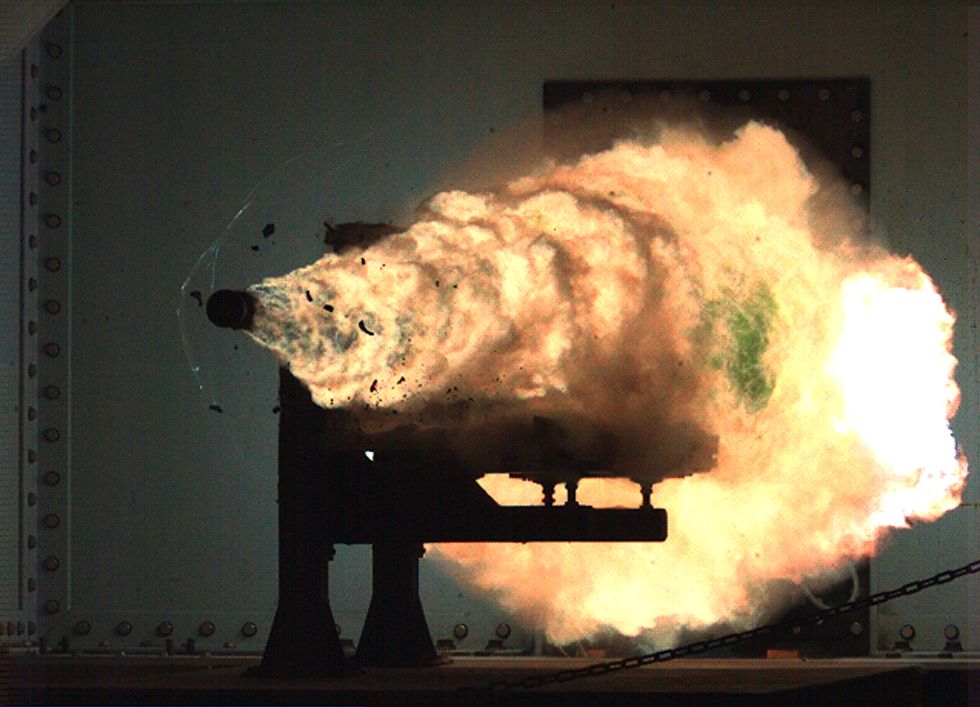

Perhaps a bigger problem is that the railgun will shred its internal components to bits if it is fired enough. You can see parts of the rails themselves erupting from the weapon as plasma when it is fired. The projectile is leaving at incredibly high velocities, and as it accelerates down the barrel the contact between the sabot and the rails simply erodes the gun itself.

As University of North Carolina physicist Mark Gubrud told Defense One:

The real limit is how much energy per shot you can deliver to the projectile and sabot without destroying the rails too fast. All that plasma that you see when the gun erupts, that's material from the rails and sabot being vaporized at the sliding contact, unlike a powder gun where the barrel isn't much eroded and the flame is from the propellant gases. I think this is what limits the total energy that can be delivered to the projectile in practice.

The issue of power is a barrier that will get smaller with time. New capacitors, more resistant materials and better pulse power storage systems could all contribute to making the railgun more efficient. Computer-aided design, 3D printing techniques and better dielectric materials—materials that don't conduct electricity but can store energy in the form of an electrostatic field—could all lead to making the EM railgun viable. As Defense One reports, Raytheon Integrated Defense Systems is already looking into a number of these technologies and working with the Navy to develop more efficient pulse power systems—big modules that store energy for the weapon.

But it's impossible to know how long it will be until the technology advances enough to efficiently power the gun we currently have. The U.S. Navy needs a solution for the near future, and it has come up with two.

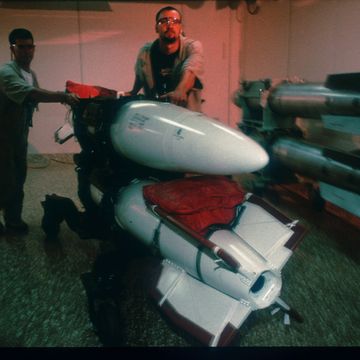

The first is to fire the railgun projectile out of conventional cannons. The Navy discovered in 2012 that they can fire the railgun projectile out of 5-inch powder guns already mounted on many U.S. warships. The hypervelocity projectile has also been tested in 6-inch guns and 155mm Army howitzers. The tungsten round won't leave the powder guns at Mach 6, but it will leave them at Mach 3, twice as fast as conventional rounds, according to Defense One.

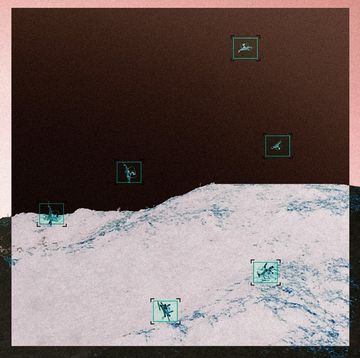

The other short-term solution is to develop a railgun that uses less power. An EM railgun that could fire a projectile at 2,500 mph instead of 4,600 mph and hit a target at 50 nautical miles instead of 100 would still be incredibly useful, especially if the Navy could mount the weapon on existing warships. A less powerful railgun still has all the advantages of being cheaper to fire and removing dangerous explosives from a ship. According to the Wall Street Journal, the Pentagon's Strategic Capabilities office has allocated $800 million to develop a "defensive capability" for the gun—i.e. making it shoot with less power for closer ranges—as well as adapting conventional weapons to fire the tungsten projectiles.

When will the railgun see action in combat? At this point, it's anybody's guess.

Source: Defense One

Jay Bennett is the associate editor of PopularMechanics.com. He has also written for Smithsonian, Popular Science and Outside Magazine.