What do you think?

Rate this book

210 pages, Hardcover

First published January 5, 2016

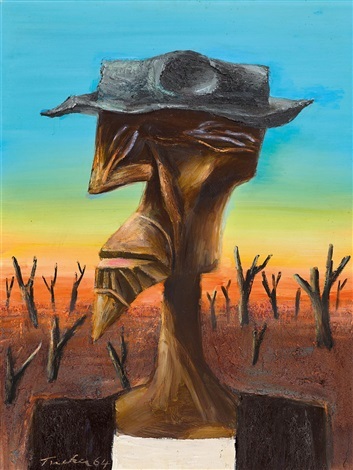

"There was no escaping the fact that I was reading a bad book by a very fine writer, but it occurred to me that this was actually a good thing. China Miéville, a writer with an international cult following whose commercial success is every bit as secure as Murakami or Franzen’s, had dared to do something that they, so far, have not. He had dared to take risks, he had dared to leave his comfort zone, he had dared to fail. And that’s precisely what he did. I find a failure of this kind far more admirable, if not more satisfying, than another safe commercial success."

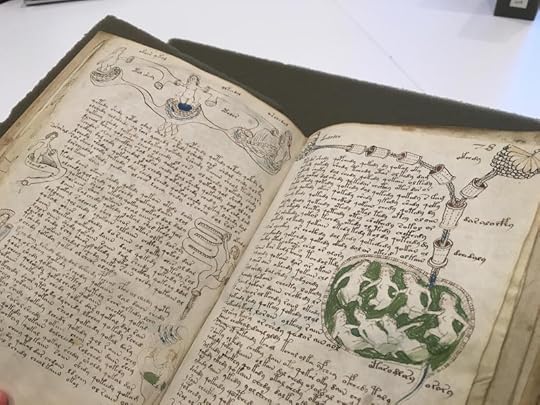

"The [second] book's for readers...It's the book for telling...You can still use it to tell secrets and send messages. Even so. You could say them right out, but you can hide them in words, too; in their letters, in the ordering on lines, the arrangements and rhythms...The second book's performance."

Houses built on bridges are scandals. A bridge wants to not be. If it could choose its shape, a bridge would be no shape, an unspace to link One-place-town to Another-place-town over a river or a road or a tangle of railway tracks or a quarry, or to attach an island to another island or to the continent from which it strains. The dream of a bridge is of a woman standing at one side of a gorge and stepping out as if her job is to die, but when her foot falls it meets the ground right on the other side. A bridge is just better than no bridge but its horizon is gaplessness, and the fact of itself should still shame it. But someone had built on this bridge, drawn attention to its matter and failure. An arrogance that thrilled me. Where else could those children live?