How Libraries Are Becoming Modern Makerspaces

They’ve long served as communal gathering spots, but these civic institutions are becoming gateways to technological tinkering.

If you could ask Ben Franklin what public institution he would like to visit in America today, I bet he would say the public library. And if you asked him which part of the library, I bet he would say the makerspace.

Ben Franklin is well known as a founder of the early subscription library, the Philadelphia Library Company, almost 300 years ago. It may be less well known that Franklin used the library’s space for some of his early experiments with electricity.

Today, perhaps taking a cue from Franklin, libraries across America are creating space for their patrons to experiment with all kinds of new technologies and tools to create and invent.

As I wrote in a short piece in the March issue of The Atlantic, called The Library Card:

Miguel Figueroa, who directs the Center for the Future of Libraries at the American Library Association, says makerspaces are part of libraries’ expanded mission to be places where people can not only consume knowledge, but create new knowledge.

The first modern library makerspace appeared about five years ago in the Fayetteville Free Library in upstate New York. Lauren Smedley, a graduate student in Library and Information Science at nearby Syracuse University, proposed the idea of bringing a 3D printer to the library. Library Director Sue Considine liked the idea and with the entire library team, built on it and created what would be the first makerspace. That was just the beginning. Today, Fayetteville’s 2,500-square-foot Fab Lab (stands for fabrication lab, and is a common name for makerspaces) has expanded to include a Creation Lab for teens and pre-teens, and a Little Makers space for the tiniest makers.

While traveling around the country for the American Futures project, I was always on the lookout for makerspaces in town libraries. I found one right here, in my own backyard, at the flagship of the D.C. public-library system, the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library.

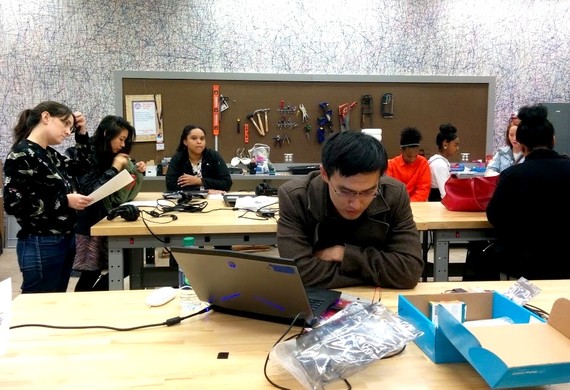

So, I signed up for a tour of their Fab Lab. At my Saturday afternoon tour, I joined a standing-room-only crowd of some 30 people, from 20-something hobbyists to budding entrepreneurs, including a family with their homeschooled pre-teens.

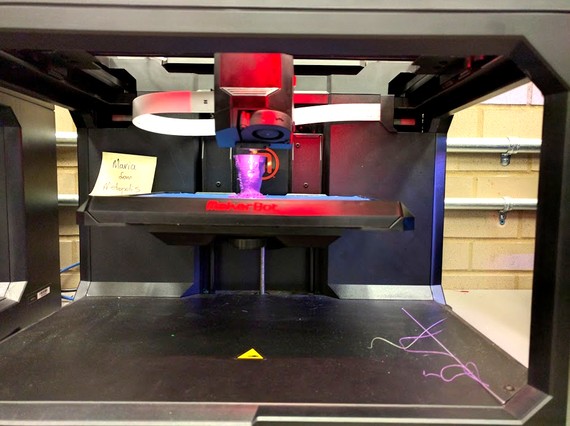

Adam Schaeffer, the hip Library Associate and a perfect match to the accessible, collaborative culture of makerspaces, gave the tour. He introduced us to the eight 3-D printers, four of which were named Kevin Spacey, Dr. Stephen Nash (I googled him; he is a professor of Systems Engineering and Operations Research at George Mason University, right here in Northern Virginia), Johnny Pie (I googled him; this is a handle for a contributor to Reddit.), and Maria the Metropolis (a robot from the 1927 sci-fi film, Metropolis). Since heavily-used, new technology like these printers are in frequent need of monitoring and repair, the lab staffers are on a first-name basis with them.

We saw the laser scanner and the laser cutter, which can etch metals, or cut cardboard, wood, paper, and even pumpkins, one of which Adam passed around. There was a wire bender, named Fender Bender Rodriguez. There was a milling machine that can make prototypes of wood or plastics or even soft aluminum.

There was a tool station along one wall, which looked more like your childhood basement tool shop, with lots of super glue, duct tape, how-to inspirational books and magazine, and a collection of old-fashioned tools. If you’re lucky, you can join Adam’s Coffee Club, a coffee station using beans sourced from spots all around DC.

Like everything else in public libraries, everything in the D.C. Fab Lab is free. (Some library labs charge for some supplies.)

There are 25 branch libraries in the D.C. public library system, in addition to the downtown library. One branch near our house, the Tenley-Friendship Library (a.k.a. the Tenleytown Library), is newly remodeled. In an equally modern step, the Friends of the Tenley-Friendship Library, looking for a project for some extra funds they had raised, decided to sponsor the first ever Maker-in-Residence program for D.C.’s public libraries.

Billy Friedele and Mike Iacovone won the competition. Billy and Mike are artists, teachers and friends, and together they started the Free Space Collective, an arts effort that is all about engaging people with their public spaces, via art.

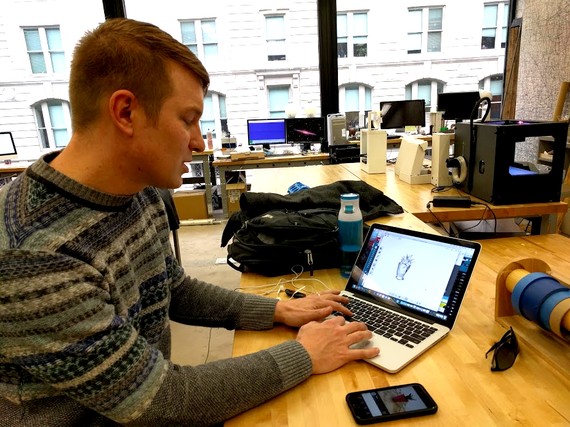

On my second trip to the Fab Lab, Billy was experimenting with transforming a photograph into a 3-D object. He was trying out the software and hardware systems that begin with a series of photos he made of a plant in a planter, and turning out an actual, miniature 3-D replica. The magic happens in photographing the object in 360-degrees, including from the top and the bottom, and sending that information to the 3-D printer to do its work. While we talked, the printer was patiently exuding the plastic fed from a spool of wire through a tiny pencil-like nib, onto the platform inside the small oven-looking printer. It was deep purple, Billy’s choice.

Billy and Mike have been focusing on different ways for people to look at their cities. The 3-D printing was a first step in speaking to the concept. The simple task that day was to take a familiar object you see around you, like a crunched-up soda can lying on the street, and inspire a new look at it. This was experimental, and who knows where it might lead. To an artist or even a non-artist like me, I say take a leap of faith here; Ben Franklin did. Every maker does, from the sophisticated technologist to the craftsy dabbler.

As artists, and as makers-in-residence, Billy and Mike are very focused on the community. They use words like “sync up” and “interact” with the residents of D.C. I asked if they would call themselves “community artists,” but Billy said that they don’t label themselves, and that it’s much less about themselves as artists and more about the experience of the community and interaction through the art.

As part of the agreement for being makers-in-residence, the pair conducts community workshops at some of the libraries. I decided to attend one last fall. About a dozen folks from the neighborhood showed up on a Saturday afternoon for a project they were calling “Walking as Drawing.”

We would create input for a collective work of art. We would all walk for about 45 minutes, starting and ending at the library, and trace our paths either on our phone app, or the old-fashioned way, by hand on printed street maps of the neighborhood. The only rule was to stick to public spaces (read: don’t cut through people’s yards). They encouraged us to store up impressions of what we noticed or felt along the way. We would reconvene to share our experiences and turn in our personal maps. Then, Mike and Billy would turn our group walks into digital art. Have a look:

I must admit, I was surprised to experience my familiar neighborhood with new eyes and ears. I hadn’t noticed a pop-up park along a street that I probably drive several days a week. Others were surprised at the sounds they heard—the trucks, the kids. We noticed the density of community spaces—besides the library, there was the elementary school, the middle and high schools, the church, the assisted living center, the public swimming pool, and more.

I would say that if the mission was to bring folks in the community together, to ask them to look at their neighborhood in a closer, different way, and to report back to share, then they completely succeeded. They produced this within the framework of art, and art they did produce.

Here is more of Billy’s work and Mike’s work.